Each guide is a journey. This cliché has by no means been extra obvious for me than it was in the course of the current and, hopefully, receding pandemic. Over the previous two years, whereas many of the world was in lockdown, I completed writing one novel and commenced work on one other, every of which transported me to locations each acquainted and unknown.

Sloth bear and hunter rock at Bhimbetka rock shelters (Credit score: Stephen Alter)

Sloth bear and hunter rock at Bhimbetka rock shelters (Credit score: Stephen Alter)

After beginning the primary guide, Birdwatching (2022), I had deliberate to go to Gangtok and Kalimpong, the place among the incidents in my story happen. This journey was scheduled for March 2020, however with the tragic and terrifying unfold of the virus, I used to be compelled to cancel tickets and depend on printed sources in addition to my creativeness. The second guide, Loss of life in Shambles, retraces an earlier journey to a fictional hill station, Debrakot, which was the setting for my first novel, Uncared for Lives (1978). Written 45 years in the past, once I was all of 20, that guide described a romantic, youthful escape into the mountains, whereas this time Debrakot serves as a backdrop for a darker, extra disturbing quest.

Large Boar Rock at Bhimbetka rock shelters (Credit score: Stephen Alter)

Large Boar Rock at Bhimbetka rock shelters (Credit score: Stephen Alter)

As I’ve usually stated, I write with my toes, notably relating to journey memoirs. The method of composing a novel is much like prolonged treks I’ve taken within the mountains. It’s achieved in common levels of roughly 1,000 phrases a day. Every morning, once I sit at my desk, I set off on a path I haven’t explored earlier than. The keyboard on my laptop computer gives stepping-stones alongside the route. One phrase leads on to the following and sentences progress into paragraphs till I lastly attain an appropriate halt and arrange camp for the evening. When writing fiction, I seldom know the place I’m headed. Most writers don’t plot out the endings of tales upfront however enable their inventive instincts to information them.

Sambhar in Satpura Tiger Reserve (Credit score: Stephen Alter)

Sambhar in Satpura Tiger Reserve (Credit score: Stephen Alter)

Whereas improper turns and detours are a part of the wandering course of, corrected or revised in later drafts, the ultimate vacation spot stays unsure till the concluding chapter.

A leopard at Satpura Tiger Reserve (Supply: Stephen Alter)

A leopard at Satpura Tiger Reserve (Supply: Stephen Alter)

In fact, many novels like EM Forster’s A Passage to India (1924) or Khushwant Singh’s Practice to Pakistan (1956) are structured round journeys. Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night time a Traveller (1979) additionally involves thoughts, a contemporary basic wherein the act of studying (and writing) provokes an unpredictable itinerary of occasions, mapped out inside the pages of Calvino’s guide itself. Not way back, I reread Sunil Gangopadhyay’s Aranyer Dinratri (1968, Days and Nights within the Forest) translated into English by Rani Ray (2010), who suggests in her introduction that the guide was impressed by Jack Kerouac’s On the Street (1957). The novel begins with 4 younger males boarding a prepare with out tickets or any predetermined vacation spot in thoughts. On the recommendation of an nameless stranger, they get down at a distant station within the jungle. Over the course of some days, they discover this semi-wild panorama, by way of the lens of city alienation and discontentment. After studying this novel, I additionally re-watched Satyajit Ray’s movie adaptation (1970), which recreates, in vivid black-and-white, the shadowy, disturbing sense of a dislocated, rootless journey.

Pachmarhi within the Satpura vary (Supply: Getty Pictures)

Pachmarhi within the Satpura vary (Supply: Getty Pictures)

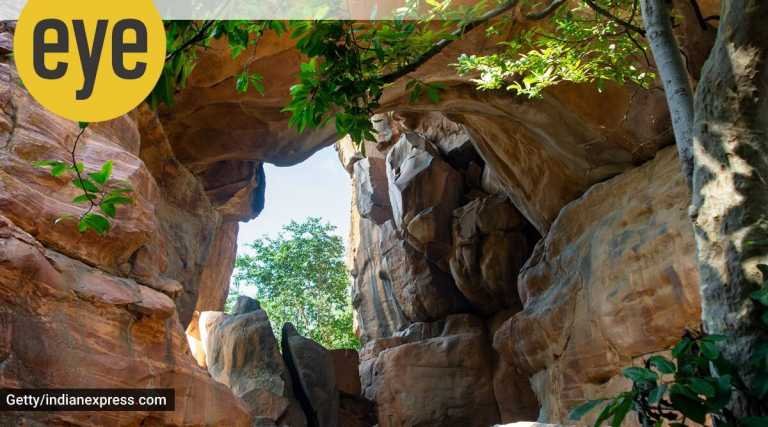

Quickly after journey restrictions had been eased, initially of this 12 months, I felt an urge to set out for locations I’d been dreaming of visiting in the course of the enforced hiatus of the pandemic. Wildlife and wild areas have at all times attracted me, and just like the characters in Aranyer Dinratri, I set off into the forest. Heading for Pachmarhi and Satpura Tiger Reserve in Madhya Pradesh, I spent every week within the jungle, looking for wildlife and visiting prehistoric rock shelters the place historical forest dwellers painted pictorial epics on the partitions of caves. Hundreds of years in the past, these nomadic hunter-gatherers felt a must narrate their adventures by way of photographs dedicated to stone. They recount the pursuit of prey, acts of bravery and cowardice, in addition to victory and celebration. Like all good looking tales, the rock artwork comprises parts of exaggeration and embellishment, just like the picture of a large boar, with horns in addition to tushes, who chases away a terrified hunter. Being a author and a traveller, I felt an instantaneous kinship to those visible storytellers who lived itinerant, unsettled lives within the Satpura and Vindhya Ranges that border the Narmada Valley.

Sloth bear cub at Satpura Tiger Reserve (Credit score: Stephen Alter)

Sloth bear cub at Satpura Tiger Reserve (Credit score: Stephen Alter)

Every time I journey, I select a guide to hold with me. On this case, I had consciously picked an previous favorite, Hugh Allen’s The Lonely Tiger (1960), which describes wildlife within the Satpura area. Amid the verdant jungles, I stumbled on residing creatures from Allen’s tales in addition to species depicted within the cave work. Encountering an impressive male leopard on one in all my outings, in addition to a sloth bear with cubs, I felt I had lastly escaped the confinement and isolation of the previous two years. Right here had been timeless tales that I might observe into an unsure, uncharted future.

Stephen Alter lives and writes in Mussoorie. His most up-to-date guide is Birdwatching: a novel